Every link in the logistics industry broke down. It will take a long time for normalcy to return.

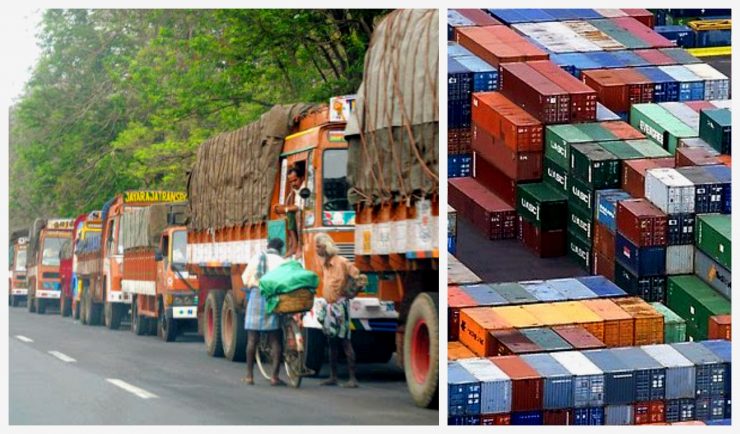

Even before Prime Minister Narendra Modi made his announcement at 8 pm on 24 March that a complete lockdown would be enforced from midnight, inter-state trucks had started piling up at different state borders. Many of these states had already announced their specific lockdown rules from the morning of Monday, 23 March and state police departments were routinely stopping every truck at the border – both from going out and coming in.

After the PM’s announcement, complete chaos ruled across the country for the first couple of days. Trucks carrying freight from one end of the country to another and passing through several states were stopped at state borders and stuck there for several days as authorities debated on whether to allow them to go forward or not. Truck associations claimed that as many as 300,000 trucks loaded with goods worth several thousand crores had got stuck at state borders. Intra-state and intra-city freight movement also came to a halt. Every logistics company – whether they dealt with shipping and freight movement from ports and airports or domestic factories to their warehouses across the country. Even the movement of goods from the company or e-commerce warehouse to the premises of the distributor and or retailers got affected because of a lack of clarity about the rules. Trucks that would ferry a farmer’s produce to the Mandi and the one that would take the vegetables bought by contractors for supplying to markets across the city were stuck or simply not available as no one was clear about the rules.

The smooth functioning of the supply chain and the logistics of goods movement is something we do not notice in normal times though it affects the availability of all goods. The car you buy in West Bengal may be manufactured in Chennai or Gujarat or Haryana but normally how it gets transported to the dealer you are buying from does not bother you.

Similarly, without a smoothly functioning transport chain in the background, your friendly neighbourhood supermarket might not get his goods on time from the warehouse on the other end of town. Factories will stop functioning, distributors will not get goods and customers will face great problems buying stuff if the chain is broken. And it got broken as soon as the lockdown was announced and confusion reigned. You will find it difficult to get your fresh fruits and vegetables and milk that you take for granted in normal times.

The confusion stemmed because the union government had given out only very broad guidelines leaving the decision on what should be allowed and what should be discouraged to states and local authorities. The Home Ministry guideline talked about essential goods without really listing out what would be considered essential and what was non-essential. (See Lockdown Diaries 5: Essential and Non-Essential Goods).

More importantly, points out Prasad Sreeram, CEO of Bengaluru-based intra-state truck aggregator Cogos Trucks, was that the policemen tasked with enforcing the lockdown treated it as a law and order problem, not a social problem. It is a sentiment echoed by Pushkar Singh, founder of LetsTransport, another intra-state and short-distance transport aggregation company, by Bhairavi Jani, executive director and owner of SCA group, a freight forwarding and logistics company which deals with both domestic and international freight and by Sunil Rallan, who is the promoter of the J Matadee Free Trade Zone in Chennai.

“Some of the truck drivers were brutally beaten up by the police (in the first couple of days because of the confusion),” says Jani of SCA group.

Some states like Karnataka and Maharashtra moved fast to sort out the confusion for intra-state transport according to most companies, with state and city authorities working out clear rules, passes for truckers to carry and protocols to be followed. Others took their own sweet time – with Andhra Pradesh and Telengana taking well over a week before they allowed truckers. Shreyas Shibulal who runs, among other things, a last-mile delivery start up called Lightning Logistics which uses a fleet of 1000 electric vehicles (EVs) to connect distributors and warehouses to retailers and handles a lot of intra-city grocery transport says that authorities in Karnataka, especially in Bengaluru, were fast and supportive. But even for his firm, which handles essential goods deliveries largely, the first couple of days were chaotic as he needed to organise passes, ensure that grocers were open before he sent out the EVs that carry his goods.

The central government itself took almost four days before it issued a notification allowing both intra-state and inter-state movement of all goods, both essential and non-essential, to move freely and complete their journeys. But many states decided to ignore them.

Even as different states started slowly opening up, new problems cropped up. For many truck owners working independently, getting passes from the authorities was a problem. For intra-state truck drivers and owners, especially those associated with logistic companies like Cogos Trucks and Lets Transport, the issues got sorted out because these companies themselves negotiated with the authorities. But for long-distance trucks already stuck in highways, there was no means of getting a pass to go on. It was a catch 22 for many of them. They could only get passes if they physically presented themselves at the office of the authorities. But equally, there was no way to drive to the office of the authority giving out passes without a pass.

There were other problems as well. Truckers found that fuel stations were often closed because either the owner of the station was afraid to keep it going because of the pandemic scare – or because the police had encouraged the pump to stay shut. Food was a huge problem as Dhabas and other eateries were shut. So was communication for long-distance truckers, many of whom used prepaid SIMs and could not charge them easily, points out Jani of SCA.

And then, the problems kept piling up. Not many truck drivers wanted to come to work because they did not want to take a risk. Others were deterred by the problems of passes, food and aggressive policemen. A few found that, after they reached their destinations, the warehouses were shut and there was no one to receive or unload the goods. Even if those problems were navigated, empty trucks returning to bases found suspicious policemen stopping them and asking umpteen questions.

Then there were social pressures. Quite often, truck drivers were dissuaded by their neighbours or families from going to work during a lockdown. Others found that villagers would not let them come back home because of fear that they would bring the disease back with them.

Logistic companies mostly say that they were working at barely 20-25% capacity. This was hindering the movement of even the goods that were available – forget the ones that were in short supply. After 10 odd days of the lockdown, even as clarity was emerging on both intra-state and inter-state movement of freight, other issues were cropping up. One was warehouses and factories that were working at a fraction of their capacities. With many factories closed and even plants manufacturing goods listed as essential working at only minimal capacities, the replenishment of goods is becoming a serious problem.

The logistic companies without exception find themselves solving all sorts of problems for their stakeholders. They had to get involved in things like getting passes for partner drivers to finding vendors for clients. Cogos Trucks’ CEO Sreeram gives an example of one of his clients, a contract manufacturing pharma company in Bengaluru. Immediately after the lockdown was announced, the contract manufacturer got a lot of enquiries from various state government departments, including the police department, whether it could make sanitizers. It could but there was a problem. It did not have labels and plastic bottles for them. Cogos Trucks had to find different suppliers for those, get permission from the police department, and ensure that the company could supply the orders it had contracted.

Other problems included negotiating with finance companies to go easy on truckers with EMIs, getting clients to pay for transport on a daily basis and not monthly as per old norms, working out safety protocols etc. Jani says there is also a recognition problem – many truckers feel they are doing essential work and taking great personal risk to keep things going during a time when the country needs them. But they are not getting the kudos that health workers are getting.

How soon can normalcy in the supply chain be restored once the lock down gets over? The best case scenario is a few months though most agree that it could be up to six months or more before things come back to normal. If they ever do.

Add comment