Is the worst over? What do the sector wise indicators of the GDP estimates show? What can the government do now?

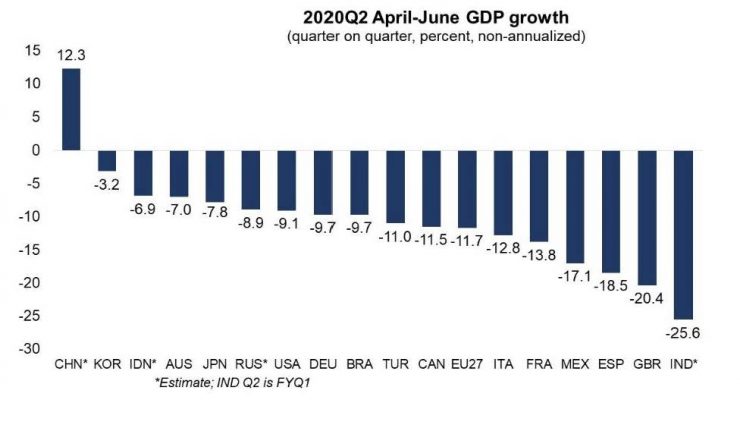

The first estimate of GDP for the first quarter (April-June) of FY20-21 showing a contraction of 23.9% compared to the same quarter of the previous financial year would not have surprised too many analysts. The stringent lockdown had brought almost all economic activity to a standstill for much of this period.

These numbers too might be flattering – as has been pointed out by the former chief statistician of India Pronab Sen in an interview to BloombergQuint, as well as other commentators. The estimates released are based on early data available, and they may not capture the full extent of the economic devastation in the informal sector. The release itself talks about the data challenges, which will have implications on these estimates.

Much has been made about the fact that the Indian economy was hit harder than that of other G-20 countries. But while that is not a happy statistic, the focus should ideally be on three questions. One, is the worst over? Two, what do the sector-wise indicators say about the problems in the GDP. And three, what can the government actually do to fix the economy.

The answer for the first question is that the worst seems to be over, provided the trajectory of transmissions does not force another equally stringent lockdown. The RBI and most economists expect the second quarter numbers to also show a contraction because economic activity had not resumed fully because of state level lock-downs that continued and still continue, with some relaxations. One can assume that by October, most of the restrictions will be lifted, but that would also depend on the condition of daily cases being detected in various states and districts. So there are hopes of the economic recovery to gain a little momentum in the third and fourth quarters of the financial year provided there are further relaxations and there is no meltdown in the financial sector now that the moratorium period is over and non-performing assets (NPAs) are expected to rise sharply.

The answer for the first question is that the worst seems to be over, provided the trajectory of transmissions does not force another equally stringent lockdown. The RBI and most economists expect the second quarter numbers to also show a contraction because economic activity had not resumed fully because of state level lock-downs that continued and still continue, with some relaxations. One can assume that by October, most of the restrictions will be lifted, but that would also depend on the condition of daily cases being detected in various states and districts. So there are hopes of the economic recovery to gain a little momentum in the third and fourth quarters of the financial year provided there are further relaxations and there is no meltdown in the financial sector now that the moratorium period is over and non-performing assets (NPAs) are expected to rise sharply.

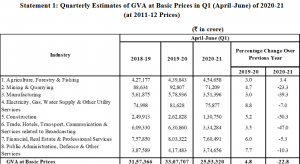

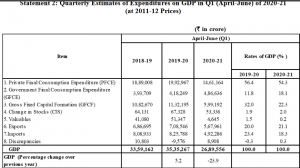

Meanwhile, the second question – what do the sector wise indicators show? The fact that construction, manufacturing, mining and quarrying, and trade, hotels, travel, communication services would be hit hard was expected. Though mining and quarrying were not locked down, labour availability and demand would have affected them anyway.

The more worrying part is that the gross value added (GVA) for public administration, defence, and other services show a drop. The expenditure figures show that, as a proportion of GDP, government final consumption expenditure has gone up. Private consumption, as a proportion of GDP, had started falling even before the lock-downs and one can expect it to remain subdued, as the full effects of jobs lost and incomes coming down start showing up in the second quarter. The big fall in gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) as a proportion of expenditure on GDP is also worrying because there can be little expectation of fresh private investment until demand picks up.

The final question: what can the government do to fix the economy? There is a huge clamour to increase government spending, both on infrastructure as well as social sector programmes. It is a most sensible suggestion except that it ignores the state of the government finances, which are in a parlous state. The rapidly deteriorating state of the fiscal situation had been pointed out almost a year ago by Rathin Roy, who was part of the PM’s Economic Advisory Council. Other economists, including former governor of RBI Urjit Patel as well as the CAG have also pointed to the government’s tendency for creative accounting to show a better fiscal position than reality. Now the spending profligacy of earlier years, along with falling revenues, is catching up with the government as it faces its biggest economic crisis. Sure it has the ability to borrow more and even monetise its debt, but even that is not going to give it enough money to spend its way out of trouble.

The final question: what can the government do to fix the economy? There is a huge clamour to increase government spending, both on infrastructure as well as social sector programmes. It is a most sensible suggestion except that it ignores the state of the government finances, which are in a parlous state. The rapidly deteriorating state of the fiscal situation had been pointed out almost a year ago by Rathin Roy, who was part of the PM’s Economic Advisory Council. Other economists, including former governor of RBI Urjit Patel as well as the CAG have also pointed to the government’s tendency for creative accounting to show a better fiscal position than reality. Now the spending profligacy of earlier years, along with falling revenues, is catching up with the government as it faces its biggest economic crisis. Sure it has the ability to borrow more and even monetise its debt, but even that is not going to give it enough money to spend its way out of trouble.

The only option then seems to be for second generation reforms to attract private investment and spur private sector economic activity, and to go in for privatisation of its remaining family jewels despite the worry that it might not be able to get the best price in this market. It does not have too many other options left.

Add comment