The spat between the union government and the states is obscuring the real questions – what are the implications of the shortfall on the stimulus measures and how will Corona affect projections for the future.

Disputes about who owes whom how much is always nasty. So it hardly surprising that yesterday’s GST council meeting where it was announced that the GST collection shortfall this year would be Rs 2.35 lakh crore and the central government would not be in a position to pay the compensation that was promised to states led to huge heartburn among states who feel they have been cheated.

The union government has taken a stand that the Coronavirus pandemic is an Act of God and could not be planned for. It has instead offered states two options for borrowing to meet their finance needs caused by the shortfall in two ways from the central bank.

The states predictably feel that the centre is cheating them. After all, at the time of passing of the GST Act, the union government had assured states of 14% growth protection for the next five years, based on a certain agreed base number at the beginning of the GST implementation period. Now trying to back out under the plea that Coronavirus is an Act of God and could not have been anticipated when the GST Act was being passed by Parliament is not a tenable argument.

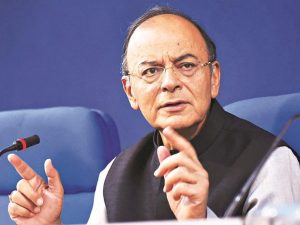

The issue is that both sides need to bear part of the blame for the problem that has cropped up now. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his then Finance Minister, the Late Arun Jaitley were rather desperate to get the GST passed in 2016. Before he became the Prime Minister in 2014, CM Modi of Gujarat had vociferously opposed the GST proposal of the then UPA2 government. After the NDA formed the government, Mr Modi changed his views about GST and wanted it implemented post haste.

The issue is that both sides need to bear part of the blame for the problem that has cropped up now. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his then Finance Minister, the Late Arun Jaitley were rather desperate to get the GST passed in 2016. Before he became the Prime Minister in 2014, CM Modi of Gujarat had vociferously opposed the GST proposal of the then UPA2 government. After the NDA formed the government, Mr Modi changed his views about GST and wanted it implemented post haste.

Just as he had opposed the GST proposal when he was chief minister of Gujarat, there were plenty of Opposition-governed states that were now opposing his proposal. The late Arun Jaitley was tasked with getting them on board and promising them anything as long as they agreed to the GST Act was being passed.

The fact is that the states made a great many unreasonable demands and after some discussion, the Finance Minister agreed to them in order to get the Act passed. The demands included multiple rates because apparently there were goods that needed to be taxed higher as they were considered premium or luxury. And also the promise to compensate states in case the GST collections did not achieve 14% growth every year based on a base figure of tax revenues per state.

It was an unrealistic promise to start with, and was too ambitious in its growth projections. The union government thought it could raise money for the shortfall compensation every year by tagging on a cess on luxury and “sin” goods. The fact that it could end up being counter-productive and lead to lower sales of these goods – and therefore lower money collected to meet the shortfall compensation apparently did not occur to anyone.

At any rate, Prime Minister Modi was happy that the Act was passed, no matter that it lead to a highly flawed GST full. He gave his midnight speech. The nation applauded.

At any rate, Prime Minister Modi was happy that the Act was passed, no matter that it lead to a highly flawed GST full. He gave his midnight speech. The nation applauded.

But from the very beginning, GST collections never met targets. Over the last two years, as the economy has slowed, they have also been going down. Meanwhile, the union government remained optimistic that things would turn around without any effort. Every year, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has been making unrealistic projects about revenues and they are being missed each time.

The centre has been delaying paying states their GST shares and the compensation amounts for some time, so it should hardly have been a surprise to any state that there was trouble looming ahead.

The squabble between the centre and states can get ugly if the states do not agree to either of the two formulas proposed by the government. Certainly, the Congress-led states; Kerala, which is governed by the Left Front, and West Bengal under the TMC government are expected to make most noise. The union government will throw up its arms and say it simply has no money to pay the states.

The states are likely to demand that the union government pays for the additional borrowings the states will need to make.

But while this fight will go on for some, the real questions are being ignored. The big question is: what does the GST shortfall mean for the stimulus package the government has announced to help revive the industry. What kind of additional borrowings will it need to go for? In which areas will the centre and states cut expenditure if they cannot raise the resources to make up for the shortfall? And finally, given that the prospects of some sectors such as travel, hospitality, restaurants, clubs and a few others are expected to be bleak for the medium term, what will it mean for GST revenue projections for the future.

It will take some time for the answers to emerge.

Add comment