The government needs to tackle a demand- as well as supply-shock now. And then it will have to deal with a financial sector on the verge of collapse.

The government is slated to release the GDP figures for the first quarter of FY20-21 tomorrow (Monday, August 31). It is likely to be an ugly picture – economists have forecasted that the first quarter’s GDP will contract anywhere between 16% and 25%.

At any rate, the GDP figures will be revised – and probably downwards – as more data comes in. Tomorrow’s GDP figures will be based on early data available, which is unlikely to have captured the full extent of the economy’s devastation.

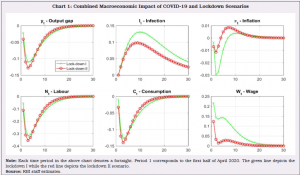

The Reserve Bank of India’s annual report that came in a few days ago points out that the signs of recovery that were seen in May and June after the lockdown was eased in several parts of the country have already lost steam in July and August because of lockdowns that were imposed again. The contraction of the GDP is therefore expected to carry on even in the second quarter. More importantly, the RBI points out that the run of the Coronavirus will change the dynamics of the world economy, perhaps permanently. That is not happy news for the government.

This year’s economy will bear the full brunt of the COVID effect with the broad consensus that the overall contraction for the whole year could be 5-7% with a few economists even more pessimistic with their forecasts. But will the next year – FY 21-22 — see a quick and sharp economic recovery? Even the RBI does not think so.

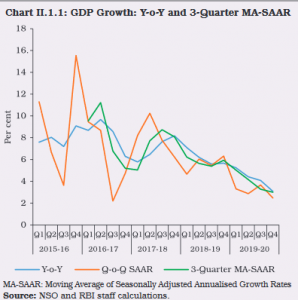

India had enjoyed several years of great growth before the 2008 crisis struck – and it was in a far better position to take steps that were needed, including a huge stimulus package. This time, we had eight quarters of successively falling growth even before the Coronavirus struck. Unemployment was already at a 40 year high, the fiscal situation was deteriorating and private consumption had fallen sharply. So the government was hardly in a good spot even before COVID.

There might be a statistical jump that flatters to deceive in FY20-21, but remember that this will be based on GDP growth over the contraction of this year. That would mean that we would just be at the same place we were in pre-COVID in terms of GDP or, at best, marginally above it. And that was not a happy place to be in. My view is that the path to recovery is going to be long, hard and, fraught with potholes and hurdles. The path ahead will test the nerves of a far smarter economy management team than we have currently.

The problem is that the government needs to deal with both a demand- as well as a supply shock immediately to get out of the current slump. One shock is bad enough but two is a nightmare especially when your finances were already in a mess even before the crisis.

The demand shock comes primarily because incomes have shrunk and jobs have been lost in almost all sectors and segments of the economy, barring the very wealthy. The initial brunt of the lockdown hit the poor and the migrant workers the hardest but as the economy opens up gradually, there is increasing evidence that while the informal job scenario is improving somewhat, the formal job losses are just about starting.

The managing director of the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), Mahesh Vyas, had pointed out that 18.9 million salaried jobs had already been lost due to COVID, out of which 5 million were lost in July alone. And remember, the jobs lost were those of people already employed. The people joining the workforce this year are facing a bleak job market. The CMIE survey suggests that job losses could hit every age group of the working-age population.

Meanwhile, the RBI report says that COVID has worsened the household savings of Indian households. This is probably because people who have recently lost jobs are now dipping into their savings to survive. Consumption and demand can hardly go up until these conditions are reversed. In some sectors such as travel and hospitality and malls, the demand destruction will take months, if not years to recover. While consumption in some areas has recovered, the full pre-COVID consumption is unlikely to return unless people feel confident about their jobs and incomes. Given the current sentiments, it could take two years or more for that to happen.

Meanwhile, the RBI report says that COVID has worsened the household savings of Indian households. This is probably because people who have recently lost jobs are now dipping into their savings to survive. Consumption and demand can hardly go up until these conditions are reversed. In some sectors such as travel and hospitality and malls, the demand destruction will take months, if not years to recover. While consumption in some areas has recovered, the full pre-COVID consumption is unlikely to return unless people feel confident about their jobs and incomes. Given the current sentiments, it could take two years or more for that to happen.

The supply shock happened initially because the abrupt lockdown in India and those implemented across the globe brought operations back to an abrupt halt. Now, as patchy unlocks are being implemented, companies are still grappling with supply chain issues, labour availability and onerous unlock protocols. The construction and manufacturing sectors are still working at sub-par capacities.

For many companies, the full pre-COVID productivity is still some time away. In many sectors, weaker companies are also shutting down – with implications on future supply once the stock in play is consumed. The biggest problem, of course, is the financial situation of companies which will be apparent once the moratorium is lifted. How many companies will be able to continue in business will be known only over the next few months. And that, in turn, could prove problematic for their lenders. As another RBI report – on financial stability – said, the non-performing assets may surge 1.5 times their March 2020 levels in a baseline scenario and even more in a severely stressed scenario.

The government’s response so far has been to announce increased spending in infrastructure projects and social programmes, including MNREGA and PM Garib Kalyan Yojana. It has also announced cheap and quick loans, especially for the small and medium industries that are the most vulnerable. Finally, it is announcing policy changes that will supposedly help domestic manufacturing. These range from licenses for television sets being imported to higher tariffs on some imported goods and finally, items that will be reserved for manufacturing in India.

The government’s response so far has been to announce increased spending in infrastructure projects and social programmes, including MNREGA and PM Garib Kalyan Yojana. It has also announced cheap and quick loans, especially for the small and medium industries that are the most vulnerable. Finally, it is announcing policy changes that will supposedly help domestic manufacturing. These range from licenses for television sets being imported to higher tariffs on some imported goods and finally, items that will be reserved for manufacturing in India.

None of those steps can be faulted in terms of intent. But as they say, the devil lies in the details and this is where the government’s ability is suspect. The government’s fiscal condition was stressed with revenues failing to keep up with projections and borrowings going up. The RBI report talks about this as have former RBI governors. Worse, it had been creative in its accounting to hide the true extent of its fiscal stress. That limits its ability to throw money at the problem by borrowing heavily, even if government debt is to be monetised towards the end of the year, as many expect. Worse, government borrowing itself creates ripples in the financial system and affects the ability of private borrowers to raise money adversely. The news yesterday that GST collection shortfall for the year FY20-21 stands at Rs 2.35 lakh will also affect the governments ability to spend on the programmes it has announced.

The bigger problem is that many of steps it has announced sound good in theory but have proved terrible in practice when they have been tried out earlier. The controls it is putting on imports can take the country back to the days of pre-economic reforms that led to shoddy products, shortages, and higher prices. Worse, they may be counter-effective in integrating into the global manufacturing ecosystem. What is needed is not more protectionism, but a set of policies that can help resolve the land, labour, local level compliance costs and productivity that is the bane of Indian manufacturing as well as taxes that provide incentives to manufacture in India.

The push to give loans freely to small and medium industries is almost sure to end up in higher non-performing assets for banks – as all previous such loan melas have shown. Former RBI governor Urjit Patel’s book – Overdraft – talks extensively about how the government’s penchant for loan melas have wrecked the banking system.

Beyond that though, the biggest worry is the state of the financial sector which was tottering even before the Coronavirus struck. With the troubles in Yes Bank, IL&FS, Dewan Housing as well as troubles in a couple of cooperative banks, the financial sector was already tottering before the Coronavirus. The government’s penchant for using the banks as instruments for executing populist schemes instead of letting them be run according to sound commercial principles have left them in a sticky spot and the RBI report points out that the system-level capital adequacy ratio could well drop sharply from its March 2020 levels. The issue is that the tax payer ends up paying for the government’s profligacy when the banks need recapitalisation. There are other hazards too numerous to mention here.

The current economic situation needs deft handling and a tightrope walk that ensures that businesses are given loans and incentives without the financial sector coming crashing down. The real question is: can this government manage that difficult task. Nothing it has done in the past six years inspires confidence that it will be able to do so.

Add comment