It is clear that not enough planning was done for the vaccination programe

The lack of planning and sheer casualness with which India’s Covid vaccination programme was rolled out is becoming increasingly apparent every day. The contradictory statements and reports coming in news publications paint a picture of a man-made mess that could easily have been avoided. The tone deaf messages from ministers only reinforce that impression

Even as the government claims that there are enough vaccines, multiple reports have come in that at least eight states have complained of low stocks. Maharashtra, which is seeing a huge surge in Corona cases said that it had barely three days stock left as it requested the union government to urgently send more vaccines. According to reports, Odisha told the union government that it had to close 700 centres because vaccines had run out. Reports of shortages came in from centres in Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Chattisgarh. Meanwhile, even in states that did not complain of shortages, people trying to get vaccinated claimed that several hospitals turned them away because of having run out of stocks.

Even while the din about vaccine shortage was becoming louder, the PMO tweeted about sending 50,000 Made in India vaccines to Seychelles. Meanwhile, the PM called for a Tika Diwas between April 11 and 14 to vaccinate as many people as possible despite multiple states complaining of low stocks to vaccinate even for a couple of days. This was just after the Union Health secretary had made the statement that only those who needed the vaccine would be given rather than everyone wanting the vaccine. Though sending the vaccines abroad was probably unavoidable – as we will discuss later – the timing of these statements was unfortunate to say the least as were the contradictory messaging.

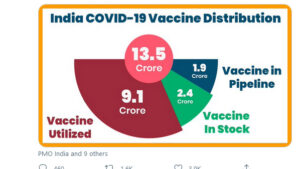

Meanwhile, the numbers presented by the Union Health Minister, Dr Harsh Vardhan, to bolster his claim that there was no shortage of vaccines did exactly the reverse. He tweeted a graphic to show that 13.5 crore vaccines had been sent out, of which 9.1crore had been utilised, 2.4 crore were in stock while 1.9 crore were in the pipeline.

Meanwhile, the numbers presented by the Union Health Minister, Dr Harsh Vardhan, to bolster his claim that there was no shortage of vaccines did exactly the reverse. He tweeted a graphic to show that 13.5 crore vaccines had been sent out, of which 9.1crore had been utilised, 2.4 crore were in stock while 1.9 crore were in the pipeline.

Those would have sounded impressive if not for the fact that the Indian population is 138 crore, of which about 85-90 crore would be above 15 years of age and therefore should be ideally vaccinated. Each, in turn, would need two doses eight to 12 weeks apart. Therefore the total requirement would be 170-180 crore vaccine doses, without accounting for any wastage, spoilage, breakages or any other such mishap. Add those and you would probably need another 10-15 crore doses of vaccine on top of that.

How did we land up in this mess? A history of tweets, public statements and other reports and materials available in public domain tell an interesting but scary story. Let us start with two of the latest. In the meeting with chief ministers of states to discuss their requests for additional vaccines and other issues, the Prime Minister told them: “You know how much vaccine is being produced. Now it is not that we can set up factories overnight. We will need to prioritise according to the available stocks. It is not that we can move stocks to one state and we will get the results. This thinking is not correct. We will have to think of the entire country.” This was reported in the national newspaper The Hindustan Times.

Only a few days before that, Poonawalla had given a candid interview to several publications where he pointed out that he would need to invest Rs 3000 crore to increase capacity and ramp up production. His suggestion was that the government of India could give him a grant of that amount because his margins were not enough to make that sort of an investment.

In an interview to a national newspaper, he claimed that he was supplying the government at a very low price, sacrificing profits for the greater good – but that such a thing could not continue indefinitely if the government wanted more stocks. More importantly was his statement that he never anticipated the demand and that if all bottlenecks (including shortage of raw material from the US and EU because they were using it for their own factories) were removed, it would take six months odd for additional supplies to start smoothly coming to the market.

The problem is that the government has so far kept its cards closely to its chest and never given answers to questions that were pertinent to the vaccination drive. For one thing, unlike the US and EU, who were monitoring promising vaccines and giving grants to build new vaccine capacities and contract manufacturing facilities even before a single vaccine was approved, India was following a wait and watch approach. The US and most of Europe were also tying up deals with vaccine developers who had showed promising Phase 2 results to snap up their total output if they got approvals after Phase 3. The US was working with Pfizer, Moderna and J&J. Great Britain and Europe were doing the same with Oxford-AstraZeneca and others.

India could not afford to do this perhaps because it is not a rich country. In September 2020 itself, Adar Poonawalla of SII had tweeted the question: Does the government of India have Rs 80,000 crore available over the next one year? Because that’s what the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare needs to buy and distribute the vaccine to everyone.”

His query was never answered and the government has remained cagey about its finances and budgets for the vaccination programme. And yes, given the state of the economy and the population that needs to be vaccinated, budgets would always be a constraint. But it was also clear that unless the pandemic was brought under control, the economic activities of the country would always be hit.

But that did not mean that it did not have some things going in its favour. Given India’s reputation for contract manufacturing facility for global vaccines, it could have actively helped contract manufacturers to tie up with promising vaccines even if it did not give them grants directly. It could also have assured them a certain amount of business if the vaccines were cleared by the regulator.

Instead, most Indian manufacturers were left to take the initiative to tie up. For example, SII, Dr Reddy and Biological E were left to pursue their own tie ups and agreements with global developers apart from the vaccines they themselves were developing.

Instead, most Indian manufacturers were left to take the initiative to tie up. For example, SII, Dr Reddy and Biological E were left to pursue their own tie ups and agreements with global developers apart from the vaccines they themselves were developing.

If it did have a plan for the total vaccines in mind, the government has certainly not revealed its full plans to most people. In the first case, after the drugs regulator, Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI) approved two vaccines – Covishield by SII, based on the Oxford Astra Zeneca vaccine, and the homegrown ICMR-Bharat Biotech Covaxin – the government took its own sweet time to negotiate final prices and place initial orders. It did not however commit to huge numbers in one go for either vaccine, preferring to place orders roughly once every month since January this year when the vaccination drive started.

A firm commitment of x million doses over six – eight months would have helped the Indian manufacturers to plan capacities better and even look for financing if capacities needed to be increased for domestic demand. No private business wants to take the risk of building huge capacities in order produce millions of doses if they were neither assured of government orders nor had the approval to sell in the open market. (The emergency authorisations mean they can only sell to the government. A general approval would have allowed them to sell directly to others in the domestic market).

Meanwhile, there has been a lot of misplaced criticism about the Prime Minister’s repeated claims of giving vaccines to neighbours and poorer countries. The truth is that these are mostly not donations by a large hearted government at the expense of Indian requirements. Most of the vaccine being exported or supplied to global countries by Indian manufacturers are either part of the licensing agreements or because of the GAVI alliance, which had given money in advance to help some Indian manufacturers build capacities in return for doses to be supplied cheaply to them. So while the government has been quick to claim credit and diplomacy, most of the vaccines going abroad were long term arrangements that cannot be broken without serious consequences.

The drugs regulator, the DCGI has also played a dubious role. It has never been clear why it approved Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin before the company had even completed enrolling enough people for the Phase III trial.

Nor is it clear why it is not speeding up approvals of other vaccines where there is enough Phase 3 clinical data available from around the globe and which are waiting for approvals in India after getting approvals from far more stringent regulators in the US and Europe.

The regulator’s requirement is something called “Bridge study” done on an Indian population if a vaccine’s entire Phase 3 clinical trials have been done in other countries. The Bridge Study is important because it needs to establish that a vaccine working on a different genetic make up is equally safe and effective for the Indian genetic make up and to also ensure the optimum dosage in Indian populations.

The issue is that in an emergency situation like this pandemic, the Bridge study requirements are told well in advance and also relaxed to an extent. Better planning between the government and the DCGI could have ensured that we got the bridge study of several vaccines done early, instead of waiting for them now. A proactive step, like the ones that have been taken by other big economies, could have helped in speeding up other approvals and this would have been good for the government as it would have several vaccine candidates available to speed up the programme.

What are the options left now? Some manufacturers such as SII are trying to ramp up capacities but it could take a few months before supplies improve. The government has also informally told SII to prioritise domestic supplies over international commitments – but this has its own perils. There are reports that AstraZeneca has sent a legal notice to SII for not meeting global commitments.

Approval of other vaccines can be speeded up. But there are price considerations as some of them would be more expensive. The Indian government has painted itself into a corner even as a fresh wave that promises to be worse than the earlier waves is unleashing havoc. A little planning could have saved it from the position it finds itself in now.

Add comment